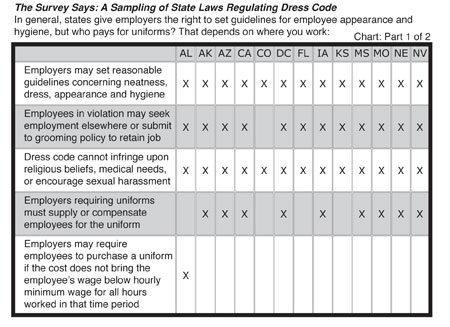

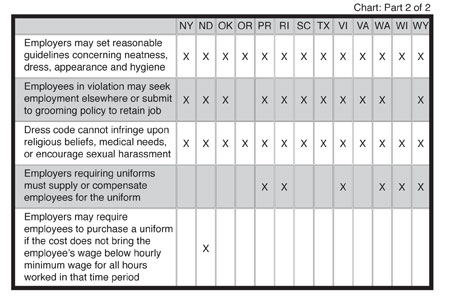

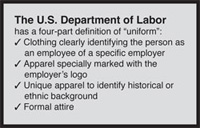

By Bernadette Doran From flight attendants to security guards, concierges to casino workers, millions of Americans wear that symbol of corporate affiliation, the uniform. But do they have to, legally? And if so, who pays for this badge of identity? Whos responsible for the upkeep? And what about dress codes stretching beyond the uniform itself to such things as body odor and facial hair? Where do the legal rights of the employer end and the personal freedom and habits of the employee begin? The answer is: Theres no simple answer. A plethora of state regulations give employers and employees different rights in different states under different circumstances, even though there are federal guidelines. And if that isnt confusing enough, employees have increasingly challenged legislation over the last few years thanks to slippery new definitions of uniform, a crunched economy thats inspiring employer and employee alike to hold harder onto every dollar, and louder proponents of social issues like gender identity. Lets start with what actually constitutes a uniform in the first place, and go to the top, The Department of Labor. It has a four-part definition of uniform: Clothing clearly identifying the person as an employee of a specific employer Apparel specially marked with the employers logo Unique apparel to identify historical or ethnic background Formal attire In recommending policy for both the public and private sector, the Department of Labor further says, If the required apparel fits into one of the above categories, it is a uniform, and the employer is required to furnish the apparel or compensate employees for the apparel. So, whether youre a maitred in a tux or a trucker in a jacket, the Department of Labor wants your boss to pay for it. This federal policy is supported by the Fair Labor Standards Act, which does not require employees to wear uniforms. However, the Act supports state laws that do make that requirement, and says that, if a uniform is required by some other law (e.g., state law), the nature of the business, or an employer, both cost and upkeep of the uniform are to be paid by the employer. But, in the grand tradition of federal/state dtente that was born when this country was, some states clearly disagree with the federal stance (see chart, pages 88 and 90), and have the right to do so. Alabama, Colorado and New York, for example, do not make employers responsible for the uniforms themselves, only for keeping warm, employable bodies in them. These state laws allow an employer to make the employee bear the cost of a uniform, although there are financial guidelines. The employer may deduct the cost over a period of paychecks but not reduce the employees wage below the minimum wage or cut into overtime compensation in the process.

For the most part, employees are required to provide their own upkeep for washable uniforms, but if dry cleaning or special care is required, the employer must pick up the tab. Also, in general, if the employer requires a uniform, the employer must pay for the time the employee changes into it if that happens at the work site. As a result of rising costs, some employers now choose the risk of a lost uniform over a higher payroll and let workers take their uniforms home to change. After more than 40 years of refusing to allow employees to take their uniforms home, Disneyland which has 10,000 employees decided to reverse its policy, says California law firm Porter Simon. It now pays less for changing time and has significantly reduced its expenses for laundering uniforms. Even small employers can potentially realize noticeable savings that way. Disney was proactive, but unfortunately, Perdue Farms was not. Employees recently put forward a class action suit claiming that Perdue failed to pay wages for the time they spent putting on, sanitizing and taking off required protective gear. The court ruling: Perdue must pay a whopping $10 million in back wages to those employees since it chickened out the first time. Can an employer further require an appearance code to be part of a uniform? Not necessarily, and well see if Lady Luck favors Harrahs Casino or former employee Darlene Jespersen, who filed a sex discrimination lawsuit against the Reno firm. After 21 years as a bartender there, Jespersen was fired for not conforming to Harrahs new Personal Best hygiene program, which requires all female employees to wear foundation or powder, blush, lipstick and mascara, as well as teased, curled or styled hair. The only requirement of male employees: Hair cut above the collar, trimmed fingernails, and no face makeup. Attorneys representing Jespersen contend that these lipstick laws are classic sex discrimination attempts, but the court has yet to rule. Meanwhile, other hygiene codes, especially based on facial hair, may dance dangerously close to race and religious discrimination. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has ruled that appearance codes forbidding bushy hairstyles and mustaches may violate Title VII because African-American men primarily wear them. Similarly, no-beard policies may be racially discriminatory because up to 80% of African-American men suffer from a skin disorder called pseudofolliculitis barbae that can only be treated by not shaving. On the other hand, a Sikh machinist legally challenged his companys no-beard policy and lost because the employer successfully demonstrated that his beard interfered with the fit of the respirator he was required to wear as protection from toxic chemicals. In general, the law has favored any dress or hygiene code thats clearly grounded in health and safety. When Is a Uniform Not a Uniform, and When Is It One? Its getting to be far more of a legal slippery slope in determining what constitutes a uniform, and therefore who pays, in certain industries. Savvy workers in restaurants and retail clothing chains are taking employers not only to task but also to court. The first harbinger of change was not a lawsuit but a request for a ruling. After getting increasing pressure from employees, a California-based restaurant chain asked the State Division of Labor Standards Enforcement to rule on its requirement for wait staff to wear Hawaiian shirts and rugby-style shorts. The chain argued that, even though it made the attire available to employees at cost, it was simply a particular style of clothing consistent with the chains theme and did not constitute a uniform. Wrong, said the state, requiring the chain to pay for the clothing as long as the chain required employees to wear it. Shortly thereafter, lawsuits started cropping up, and Ambercrombie & Fitch was the first to come under attack. Californians who worked for the clothing retailer sued, alleging that the companys Appearance/Look Policy was used to require store employees to buy and wear the companys clothes without reimbursing them, against state law. The August 2003 ruling forced Ambercrombie to dole out $2.2 million to 11,000 employees (about $200 to $500 per employee) in payment for the clothing they were required to wear, and the corporation reversed its policy as well. No doubt inspired, or at least emboldened, by that victory, three class-action lawsuits have just been brought against other giant retailers by California workers, including The Gap/Banana Republic, Polo Ralph Lauren, and Chico s. All three retailers have wardrobing policies that require employees to buy and wear their branded clothing on the job, and for some long-term employees, the cost has run into tens of thousands of dollars. Theyve all been caught red-handed in violating California law, which is very strict in regard to uniforming, says attorney Patrick R. Kitchin in an exclusive interview with Made to Measure. Kitchin, along with attorney Daniel Feder, are representing current and former employees in all three class action lawsuits. Kitchin says theres a double whammy of state regulations against this practice. First, from the California Code of Regulations: When uniforms are required to be worn by the employee as a condition of employment, such uniforms shall be provided and maintained by the employer. The term uniform includes wearing apparel and accessories of distinctive design or color. Second, according to Kitchin, is a violation of a very old Labor Code: No employer, or agent or officer thereof, or other person may compel or coerce any employee, or applicant for employment, to patronize his or her employer, or any other person, in the purchase of a thing of value. The latter is really a very old anti-company town, anti-coercion statute that prevents a company from forcing employees to, in effect, give back all their wages, said Kitchin, adding that the effects of the wardrobing requirements have been financially disastrous for some employees. For example, a new employee at a Ralph Lauren store was required to buy an $1,800 blazer on day one as a cashier, with payments deducted from his future earnings for six months. Another employee told us he was literally taking home no money while he paid off the clothing he was required to wear. Even though these are national retailers, the lawsuits are being brought against them only by California employees, based on California laws but as is often the case, as California goes, so goes the nation. Is worker empowerment a new backlash against a Republican government that has been strongly biased toward the corporation? I dont know, says Kitchin, but the folks were representing make a very strong argument for protection, and Ive been amazed at how supportive the media has been. The New Victor/Victoria Laws Another new spate of dress code questions and legal issues cropped up in 2003, owing to shifting social and sexual values in America or, at least, a shift in addressing them. American Airlines added Workplace Guidelines for Transgender Employees to its employee dress code, incorporating special rules regarding gender identity. Say the guidelines, Gender identity applies only to those individuals who, with the documented support of medical or psychological professionals are changing or have changed their physical characteristics to facilitate personal and public redefinition of their sex as opposite that which they were assigned at birth. How does that affect appearance standards? Plenty, when it comes to the Real Life Experience stage of transgendering: Employees who are transitioning are required, prior to surgery, to assume the role for their reassigned gender. This process is known as the Real Life Experience part of which is dressing in the reassigned gender role. A transitioning employees attire should remain professionally appropriate to the office in which they work and the job they hold. The same dress codes and rules for behavior apply to transgendered as to other employees. If, as a manager, you are concerned about the appearance your transgendered employee will present when she or he starts coming to work in the other gender role, ask for a picture of him or her in professional attire. Last August, ex-governor Gray Davis included the transgendered as a new, protected category under the Fair Employment and Housing Acts anti-discrimination provisions, making California the fourth state to do so in a year (the others were Minnesota , Rhode Island and New Mexico ). Attorney Laura Maechtlen provides an analysis on the Cook Brown LLP, Web site: While employers will be able to require employees to comply with reasonable workplace appearance, grooming and dress standards consistent with state and federal law, they must allow employees to appear or dress consistently with their gender identity… For example, if an employer hires Michael who subsequently wishes to work and dress as Michelle, the employer cannot discriminate against that individual for the change in his/her gender appearance, provided the employee otherwise complies with the employers dress code. This means that if the dress code imposes a length requirement on skirts, Michael/Michelle must be allowed to wear a skirt but can be held to the same length limitation as other employees. Confusing? Legally intimidating? You bet. To be on the safe side, employers might take their lead from Porter Simon, a law firm in the little mountain town of Truckee, Calif. . Their only dress code: Dont show up wearing anything smelly or with holes in it. Pretty hard to argue with that. |

| Above story first appeared in MADE TO MEASURE Magazine, Fall & Winter 2004 issue. All rights reserved. Photos appear by special permission. |

| Halper Publishing Company 633 Skokie Blvd, #490 Northbrook, IL 60062 (847) 780-2900 Fax (224) 406-8850 [email protected] |