Uniforms of army soldiers must meet certain standards and challenging requirements. The uniforms must be durable enough to survive multiple washes, resist fires, and insects among others.

However, today’s uniforms do not meet such requirements. In a bid to come up with such multifunctional uniforms, scientists have come up with a unique way to create flame retardant and insect repellant fabrics without using toxic substances.

These research results will be unveiled at the American Chemical Society (ACS) Fall 2020 Virtual Expo.

“The (U.S.) Army presented to us this interesting and challenging requirement for multifunctionality,” says study leader Ramaswamy Nagarajan, Ph.D. “There are flame-resistant Army combat uniforms made of various materials that meet flame retardant requirements. But they are expensive, and there are problems with dyeing the fabrics. Also, some of the raw materials are not produced in the U.S. So, our goal was to find an existing material that we could modify to make it flame retardant and insect repellent, yet still have a fabric that a soldier would want to wear.”

Nagarajan’s research group primarily focuses on sustainable green chemistry, and hence, used nontoxic chemicals and processes for the study.

They chose to modify a commercially 50-50 nylon-cotton blend as the material is inexpensive and has the properties of comfortability and durability. However, the material does not repel bugs and is also labelled as high fire-risk.

“We started with making the fabric fire retardant, focusing on the cotton part of the blend,” explains Sourabh Kulkarni, a PhD student who works with Nagarajan at the University of Massachusetts Lowell Center for Advanced Materials. “Cotton has a lot of hydroxyl groups (oxygen and hydrogen-bonded together) on its surface, which can be activated by readily available chemicals to link with phosphorus-containing compounds that impart flame retardancy.”

They also elected to use phytic acid, a non-toxic substance that is abundantly found in seeds, nuts, and grains. They also tackled the insect issue by using permethrin, a non-toxic insect repellant. Both the substances were successfully attached to the fabric’s surface molecules using methods like plasma-assisted deposition through trial and error.

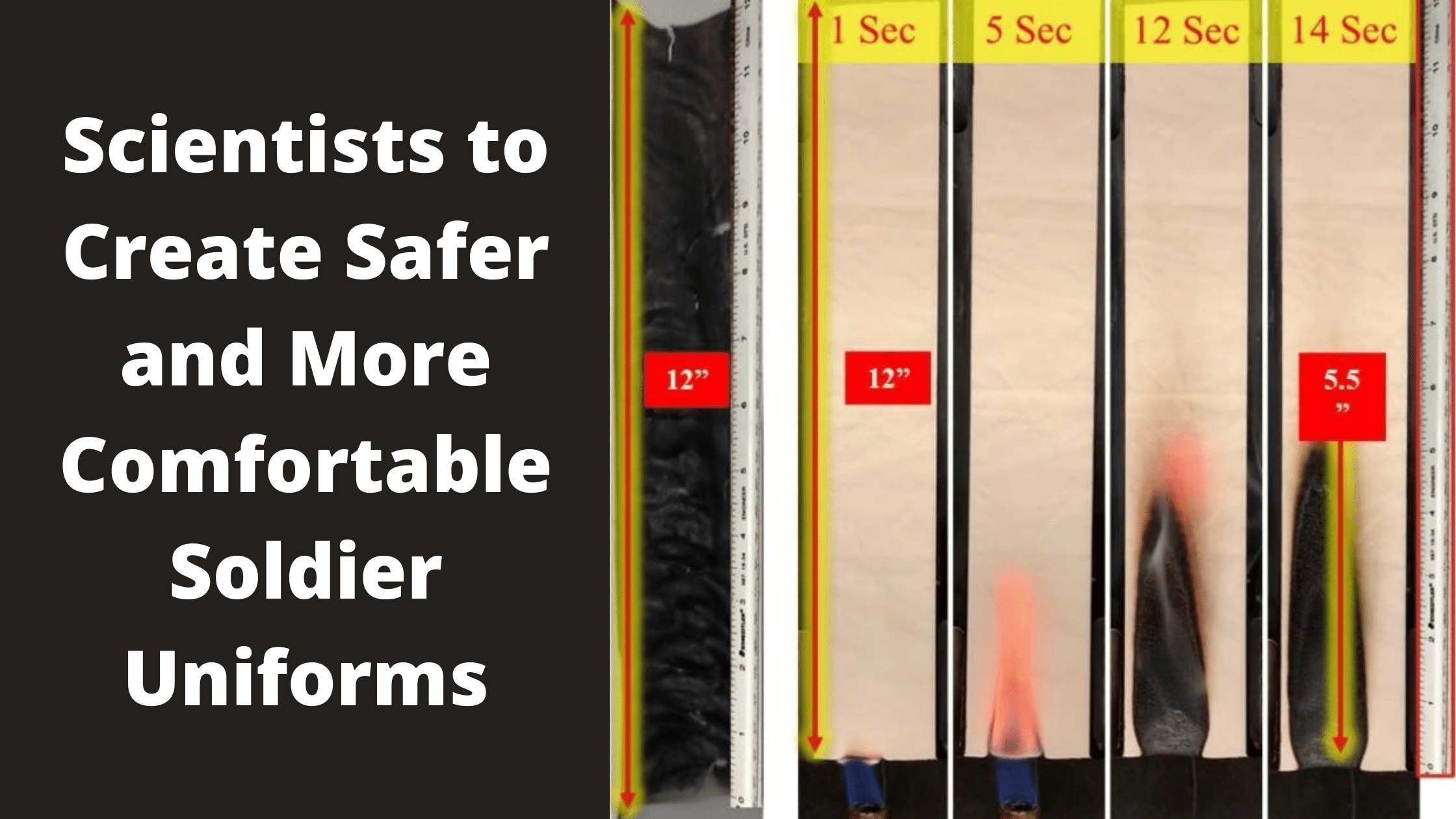

The modified fabric performed at least 20% better than an untreated fabric in the vertical flame test and also showed 98% efficacy against live mosquitoes.

“We are very excited,” Nagarajan says, “because we’ve shown we can modify this fabric to be flame retardant and insect repellent—and still be fairly durable and comfortable. We’d like to use a substance other than phytic acid that would contain more phosphorous and therefore impart a greater level of flame retardancy, better durability, and still be nontoxic to a soldier’s skin. Having shown that we can modify the fabric, we would also like to see if we can attach antimicrobials to prevent infections from bacteria, as well as dyes that remain durable.”